The bones that make up the forefoot are those that are last to leave the ground during walking. The Forefoot is composed of the metatarsals, phalanges, and sesamoids. The five bones of the midfoot comprise the navicular, cuboid, and the three cuneiforms (medial, middle, and lateral). While the midfoot has several more joints than the hindfoot, these joints have limited mobility. The Midfoot begins at the transverse tarsal joint and ends where the metatarsals begin -at the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. The bones of the hindfoot are the talus and the calcaneus. The Hindfoot begins at the ankle joint and stops at the transverse tarsal joint (a combination of the talonavicular and calcaneal-cuboid joints).

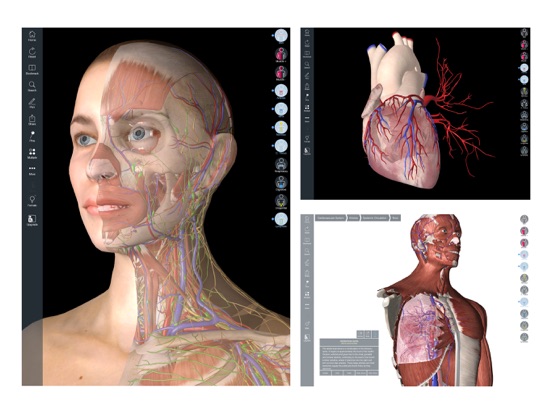

Additionally, the lower leg often refers to the area between the knee and the ankle and this area is critical to the functioning of the foot. The foot is traditionally divided into three regions: the hindfoot, the midfoot, and the forefoot (Figure 2). These will be reviewed in the sections of this chapter. There are a variety of anatomical structures that make up the anatomy of the foot and ankle (Figure 1) including bones, joints, ligaments, muscles, tendons, and nerves. With a good grasp of foot anatomy it readily becomes apparent which surgical approaches can be used to access various areas of the foot and ankle. For those conditions that require surgery a detailed understanding of anatomy is critical to ensure that the procedure is performed efficiently and without injuring any important structures. Therefore a basic understanding of surface anatomy allows the clinician to quickly establish the diagnosis or at least narrow the differential diagnosis.

Anatomical structures (tendons, bones, joints, etc) tend to hurt exactly where they are injured or inflamed. Most structures in the foot are fairly superficial and can be easily palpated. A solid understanding of anatomy is essential to effectively diagnose and treat patients with foot and ankle problems.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)